Economic Development: An Integrated Approach

Overview of Approach

Economic development planning needs to ensure comprehensiveness, thoroughness, and completeness in the analytical phase. Only then can sound strategies and policies be drafted that will be unique to the requirements of the country/region being studied.

There are a number of fundamental issues that must be addressed in the context of drafting an economic development plan:

-

Narrow regional economic bases. Regions in developing economies are often characterized by large isolated enterprises–assembly operations, processing facilities–unconnected to other enterprises in the local economy, giving rise to a lack of industrial diversity in the local economy and creating significant vulnerability to economic cycles.

-

Vertically integrated, non-dynamic industries. Many enterprises in regions undergoing the transition to a developed economy are vertically integrated and isolated from suppliers and buyers. Distribution is typically arranged by central authorities with little concern for productivity or innovation. This absence of connectiveness to markets hinders adaptation and growth.

-

Poor Supporting “soft and hard” socio-economic infrastructure. The lack of socio-economic infrastructure resources to support economic development and accelerate social development is a critical shortcoming in several economies. As a result potential wealth generators (private industries and state enterprises, for example) must frequently rely primarily on their own capacities for specialized training, access to technology, and financing–if they have the resources.

-

Limited access to global information. Compounded by limited accessibility to global information, enterprise leaders are frequently not attuned to global markets, leaving a legacy of insufficient tools, information, and institutions for economic planning that takes advantage of arbitrage opportunities in global markets expeditiously.

The economic strategy approach developed below is to address the concerns of such issues as listed above. The approach has been used in different regions, countries, states and provinces around the world and represents a new paradigm for economic development. Briefly stated, the elements of this paradigm are that:

-

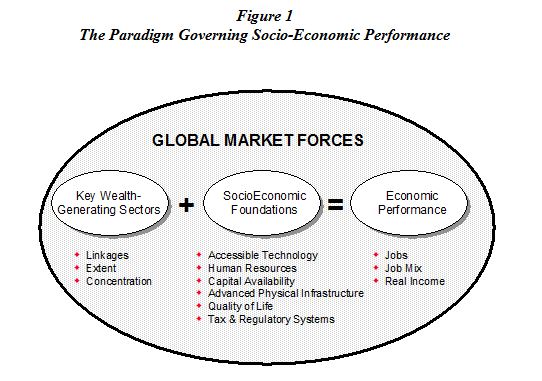

Soft” and “hard” economic infrastructure–which are the country’s sources and suppliers of technology, human resources, financing, communications and quality of life–are the foundations that provide an economic area with competitive advantage over others. The key wealth generating segments of an economy are enabled to compete and develop comparative advantages by these sources or “foundations” of economic infrastructure. To lay the path for an advanced and adaptive economy, a country or region must make investments in economic infrastructure that will link closely to the dynamic needs of these wealth generating segments.

-

Learning how global markets shape wealth generating segments and competitive requirements is essential to a growing and adaptive economic region. A country or region needs to examine its public and private policies and investments in terms of how well they respond to changing global markets and market forces.

-

Collaborative public-private actions and institutional innovation–within and between the public and private sectors–enables a socio economic entity to build competitive advantages and become competitive in the global economy. Countries that have the flexibility and adaptiveness to work together to understand socio-economic needs, define shared concerns and collaborative actions do much better in the global economy.

-

Key wealth generating segments of the economy function in a complex network of users and providers of products and services. In other words, they function best in “clusters” of activities which give the economic milieu they function in their source of high-value-added and adaptiveness. Countries need to move from pursuit of single factories or narrowly defined segments to more groupings that can enable regions within the country to “capture” more value-added or better link or “network” with global industries.

The next section describes and illustrates the methodology and approach of planning for a New Economy model of development.

An Economic Development Approach

This paradigm is not proposed de novo. Similar methods have been applied in transitioning economies from Tianjin, China to Maribor, Slovenia and Bratislava in the Slovak Republic. These same methods have been applied to Hong Kong, Osaka, and the Silicon Valley and has been applied lately to Malaysia, Morocco, and Campeche, Mexico.

The key lesson from these experiences is that economic strategy is “about” the process of changing the behavior of markets, institutions and individuals, not simply plans or policies. Therefore, the thrust of the approach needs necessarily to work with government and business leaders to energize a process of strategy development and change that will result in a vision, strategies and mobilization of the country for action along several socio-economic dimensions simultaneously.

Socioeconomic strength implies sufficient internal diversity and dynamism to continually re-channel human resource, technological and other fundamental resource structures in an economy in response to market pressures and opportunities. More importantly, economic development today does not necessarily imply high density development or unsustainable development. What it does imply is the development of a sustainable “economic ecology” that is dynamic and adapts overtime.

The leadership from the business and government community can catalyze a process of innovation-based economic development that reaches across their economy.

The elements underlying a New Economy paradigm needs to factor in some key themes:

-

Key wealth-generating segments, whether industrial, service-oriented, or institutional drive a country’s economic and social development

-

Soft and hard economic and social infrastructure should enable and support the development of these key segments

-

Global demand should inform actionable plans taken

-

Collaborative public/private action is the key to mobilizing changes in the institutional dynamics of the economy.

At the core of the paradigm linking these elements is the notion that a country’s ultimate economic performance and social enhancement is driven by the inter-relationships between socio-economic foundations and its wealth generating segments. (Figure 1).

Successful countries have been able to mediate these relationships, in the face of global market challenges, led by effective public/private mechanisms calling for change.

These new rules are explored below.

Key Wealth Generating Segments Drive Socio-Economic Development

Wealth generating segments, whether industrial clusters with concentrations of interdependent firms in related industries, service-oriented sectors that enable the smooth functioning of commerce, or public sector institutions that produce real goods and services, drive development. Ultimately, these wealth generating expand the employment base and provide income flows.

In each segment there are leading agents producing the final good or service that are supported by a host of suppliers of components, raw materials, and other support services. Within each segment, cooperation between the leading agents and supporting industries motivates buyer-supplier linkages that spur innovation and efficiency. The effect of all these networks of interaction multiply throughout the economy and generate new business, new production, and new commerce.

These segments usually are the most innovative and competitive, possibly even setting prices and trends in markets. Countries characterized by single plants and few segments are very vulnerable to economic cycles and competition. They generate fewer jobs, since they lack suppliers. Whether a community is dominated by a textile mill or a automotive facility, unless there is the natural economic ecology of market-driven buyer-supplier relations, the economy is continually vulnerable to market shifts and administrative cut-backs or changes in priorities.

The highest achievement of an economy is a diversity of segments that continually evolve and “seed” other new segments, always adding value as well as employment and wealth.

Emerging segments may be able to be seeded in a particular region and grow to form high employment, high wage concentrations. Achieving this requires looking beyond the potential for commercializing a technology and more towards understanding how technology-based businesses can begin to buy and sell from one another and create local economic synergy (as was the case in the Silicon Valley and route 128 in Boston). This is the ultimate challenge for any region that wishes to be considered a developed region. Can its leadership organizations, business associations, and trade houses become a catalyst in the formation of emerging segments; not simply single firms.

“Soft” and “Hard” Economic Infrastructure Provide the Country with Comparative Advantage

Wealth generating segments evolve because the ingredients that enable innovation are present. Every economy comprises a set of systems that “deliver” these inputs to the economy. These systems–the soft and hard economic infrastructure or foundations–are provided by public and private institutions, whose qualitative measure is their awareness and responsiveness to market demand. One segment can be a source of economic infrastructure to another cluster.

There are six categories of socio-economic foundations that are vital to the successful evolution of an economy. These include:

-

Availability of skilled workforce (preparation, advancement, renewal): The capacity to prepare, advance and renew skills as measured by occupational patterns, educational expenditures, educational outcomes, skill levels, higher education participation, value-added per worker, measures of entrepreneurial activity, and training expenditures for different levels of workers;

-

Adequacy of financial capital (initiation, expansion/modernization, restructuring): The capacity of an area to finance initiation, expansion, modernization, and restructuring as measured by loan activity, venture capital, small business capital availability, presence of national or international financial institutions;

-

Advanced physical infrastructure (communications, transportation, environment/facilities): The capacity to transport, communicate and operate as measured by expenditures on and condition of road, water, sewage, and other basic infrastructure; level of telecommunications/infrastructure capability; export and air traffic infrastructure;

-

Achievable quality of life (housing, social/health services, recreation/culture): The capacity of an area to supply housing, social and health resources and entertainment as measured by relative supply of housing, cost of living and purchasing power; air and water quality; health care access and cost; the extent of social ills like unemployment, poverty, crime; environmental and recreational amenities;

-

Acceptable tax and regulatory system (regulation, taxes, administrative efficacy): As indicated by tax rates and distribution, degree of progressivity, tax capacity and effort, revenues per capita, presence of key regulations, overall extent of regulatory burden

-

Access to technology (discovery, development, deployment): The ability of an economy to discover, develop, and deploy technology as measured by R&D investment, patents, presence of R&D institutions, productivity, and R&D spending.

Each foundations element has qualitative and quantitative measures of their capacity and responsiveness to the key wealth generating segments. Measures may include: output levels (graduates, patents, value added, loans to small businesses), growth (rate of change over time) and quality (specific measures linking infrastructure to regional industrial performance). Measures can show characteristics of demand and supply.

A country or region may already have “good scores” on some of these measures which include indicators of the level of activity and its quality. However,what makes an economic region succeed is the productive linkages between economic infrastructure and the market place. In fact, much economic infrastructure is efficiently provided by the market system, and only services where there are significant problems in scale-economies are left to government. A defining characteristic of a developed country is one whose socio-economic infrastructure functions so well that it constitutes an economic ecology in which soft and hard infrastructure is always evolving to meet market needs.

In some cases, generating a comparative advantage in economic infrastructure is viewed as a Catch-22: How can you have a good foundation when you do not have industry generating income and taxes to pay for it? History has shown that those who started by investing in their socio- economic infrastructure and making their development a continuing priority have had higher value-added and more adaptive economies. The Silicon Valley was such a case, as was Route 128-Boston, Tokyo, and Hong Kong. Other regions have come more lately to this recognition, such as Malaysia, Guangdong, China; Singapore; Austin, Texas; Portland, Oregon; Research Triangle, North Carolina; and others.

The challenge facing regions aspiring to similar goals is to develop a regional vision of the necessary soft and hard economic infrastructure and commit to investing in it for the future.

Global Economic Demand is Critical to Most Local Economies

There are no economies that are fully insulated from the shifts in supply and demand in the world economy. Understanding the structure, size and dynamics of markets in the global economy will be essential for a region to define threats and opportunities and build both its wealth generating segments and corresponding socio-economic infrastructure needed to create an economy with high employment and high-quality jobs. The future of developing countries/regions, will be significantly shaped by global trends–whether the end of the cold war or the shift of industries, such as automotive or textiles from one region of the world to another. Global trends define the business of every local economic stakeholder.

Global trends offer opportunities that can be leveraged. For example, many industries based in other countries are increasing their exports at rates that are fast bringing them to a “threshold” where they are likely to seek new design, engineering and manufacturing bases. This bodes well for the region that anticipates these trends (knowing the “thresholds”) and positions itself with these industries as a region offering the best advantages in economic infrastructure. This threshold represents a breakthrough in regional marketing which has been traditionally guided by poorly informed industrial recruiting programs.

A developed country will also become an international center in almost every instance. They are developed because they are, by definition almost, attuned to global markets and serve them in a variety of important ways – as entrepots for high value-added products and business transactions or as international centers of information, and research and development. Developed countries are not worthy of the name if they are not global in outlook and demand-driven in practice.

Public/private Collaborative Governance is the key to mobilizing changes in the dynamics of the economy.

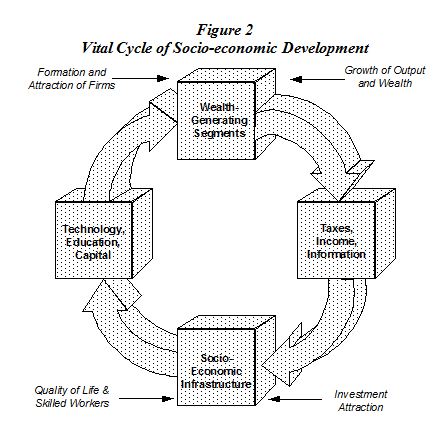

Regions with successful economies have a history encapsulated in a “vital cycle”. This vital cycle represents a pattern of relationships between economic producers and suppliers of soft and hard economic infrastructure in which each contributes to the development of the other (See Figure 2). Where there is a vital cycle, economic resources and innovative institutions produce and draw into the country technology, skills, financing, physical infrastructure and quality of life needed to stimulate formation, expansion and attraction of the wealth generating segments of the economy. The healthy industrial base, in return, provides tax revenues and local expenditures that renew and enhance the country’s economic infrastructure. Moreover, this positive feedback loop results in a continuous improvement process in which the competitive economic segments stimulate innovative socio-economic infrastructure and vice-versa.

When the vital cycle becomes stagnant or collapses, investment in economic infrastructure declines, industrial competitiveness decreases and resources needed to reinforce the adaptability of the country become scarce. Making a breakthrough that turns a vicious cycle into a vital cycle, and sustaining a vital cycle over time is a challenge that depends on the quality of both private and public leadership. No one sector can be fully responsible for this dynamic – everyone who participates in the economy plays a part in maintaining and improving its health and performance.

For these reasons, cooperation within and between the public and private sectors is what enables regions to build comparative advantage and become competitive in the global economy. As mentioned earlier, the efficiency of any economy is not strictly the product of government policies and programs but of the way that markets, institutions and individuals collectively behave. The lessons learned from Japan and Europe about collaboration suggest that when business and government focus together on mutual problems or common concerns, they can create growth for all concerned. The reverse is exemplified by the circumstances in Eastern Europe.

Building the basis for a vital cycle requires shifting our understanding of economics from being a case of public versus private sector to a mind-set of collaborative strategy, where every organization is viewed as contributing to rather than hindering the performance of the economy. In collaborative strategy, we realize that everyone governs and controls resources. As they produce goods and services, companies in the region hire and pay benefits, produce and consume R&D, finance and use financing, build and consume physical infrastructure and contribute to, as well as benefit from, enhanced quality of life. Government is another actor in the economy which has attributes of an economic producer as well. In recognizing the contributions to the economy that all sectors make, the process of collaborative strategy becomes a logical and necessary basis for building a next generation economy.

Collaborative Governance requires four basic elements:

-

Diagnosis and stimulus – to mobilize action by leaders and stakeholders

-

Leadership – stewardship on quality control and priority setting

-

A process of stakeholder-driven cooperative work – that defines common problems and solutions around which actions can be organized and implemented by responsible stakeholders

-

Ongoing implementation support – for existing and new initiatives acknowledging and rewarding small victories to maintain forward momentum.

The thrust of new thinking in economic development needs to combine collaborative governance, develop strategic economic planning, and build on the best of a country’s or region’s economic and political leadership, such as those found in cooperating chambers, districts and municipalities, development organizations, public utilities, corporations and academic institutions. If a region in this fashion it will have the opportunity to begin to build a collaborative governance process that will grow from a catalytic center outwards to an increasing number of stakeholders, bringing more participants into the process who will play responsible roles. The effort would catalyze an outward oriented economic development process for the region/nation.